Lessons from long-lived businesses

What happens when businesses treat “sustainability” as something that lasts centuries?

The business world tends to fetishise the startup: young, vigorous, aiming to scale as big as possible as quickly as possible, its founders looking for an “exit” or a “liquidity event” almost as soon as they found the business.

For as much as they create enormous value for their shareholders, and sometimes create value for society too, these businesses and the scaling model they operate under have one crucial flaw: they either don’t exist for long enough to pay for their externalities – their impact on the wider world – or they get big enough to capture regulators and avoid paying for them that way instead. Either way, this scale-first, short-termist approach encourages an extractive and exploitative view of the world and its natural and human resources.

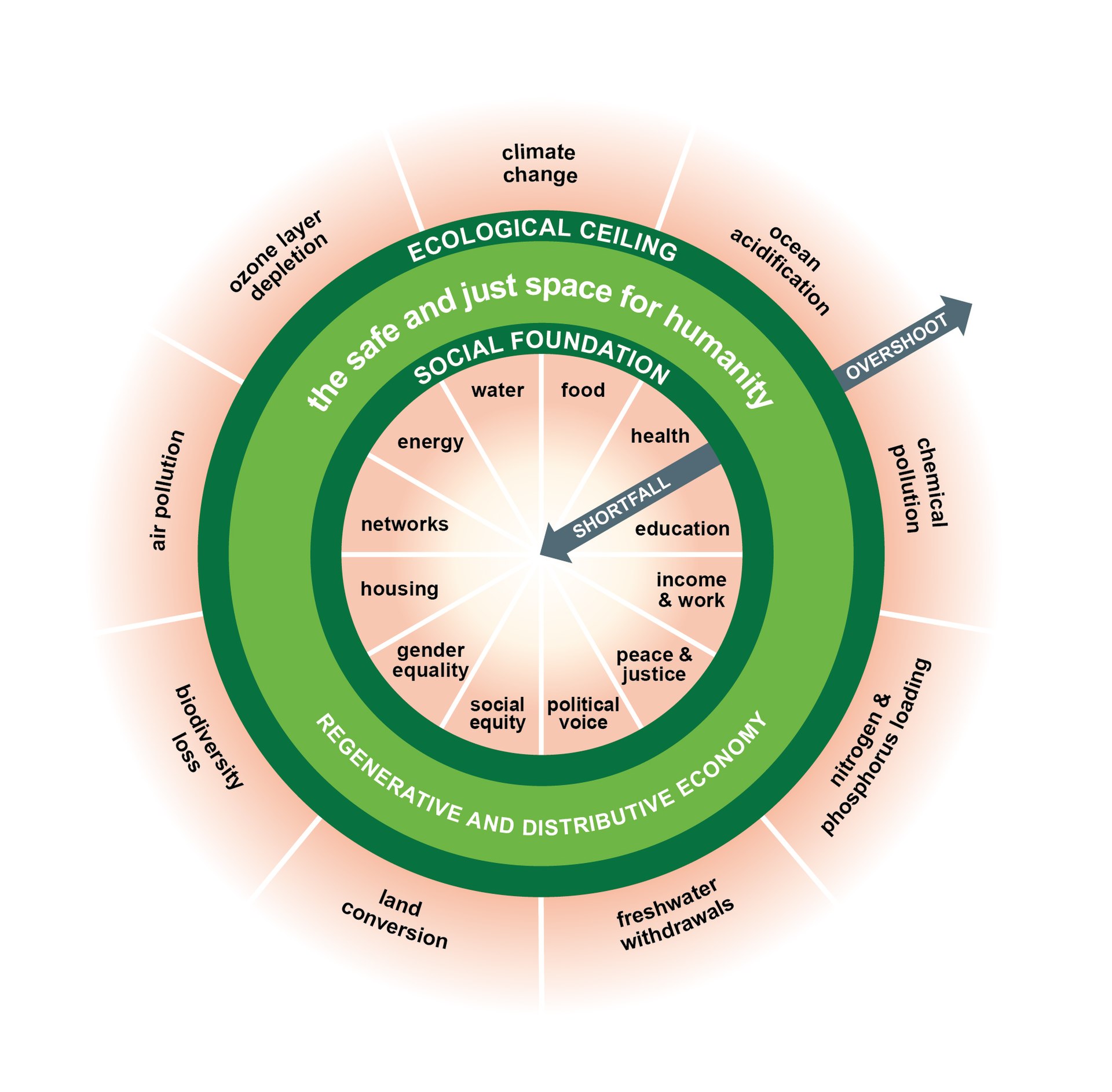

In 2017, economist Kate Raworth outlined the idea of “doughnut economics”: the idea that there is a level below which the economy and economic development should not fall (one in which people are housed, fed, clothed, educated, and so on) and also one above which the economy should not rise (one in which resources are depleted faster than they can be renewed, and in which the climate and ecosystems are thereby destroyed). Humanity, in other words, should seek to live within the “doughnut” between these two extremes:

Short-termist, scale-first businesses that seek to conquer the world are hard to square with the idea of a sustainable existence “within the doughnut”; they’re virtually guaranteed at some point to smash through the ecological ceiling.

What would it look like to run a business that sought to remain within the doughnut, and to do so for as long as possible – aiming to exist sustainably for generations, centuries even, in a way that doesn’t deplete and destroy the planet?

It’s not difficult to imagine this opposite approach to business, because it exists throughout the world already.

Japan is the clichéd epicentre of ancient businesses, and it’s a stereotype that’s borne out by the facts:

“The country is home to more than 33,000 [businesses] with at least 100 years of history – over 40 percent of the world’s total, according to a study by the Tokyo-based Research Institute of Centennial Management. Over 3,100 have been running for at least two centuries. Around 140 have existed for more than 500 years. And at least 19 claim to have been continuously operating since the first millennium.”

These centuries-old businesses are for the most part, as you might expect, in fairly stable industries. For centuries the oldest company in Japan was Kongō Gumi, a specialist in the construction of Buddhist temples – not exactly cutting-edge architecture. The list of the oldest companies in Japan is peppered with inns, breweries (of beer, sake, and soy sauce), and other reliable, always-in-demand trades. But it also includes some more surprising, higher-tech businesses – like Nintendo, founded in 1889 as a playing cards business and only diversifying into video games in the 1970s.

Japan calls these businesses shinise, and they occupy a particularly prestigious place in a Japanese society that values tradition and longevity in more general terms. To buy from a shinise is to demonstrate your impeccable (and conformist) taste, whether you’re buying sake, stationery, salted squid guts or metalworking components.

Ancient businesses aren’t just a Japanese quirk, though. Germany is home to hundreds of multi-generational businesses, from the medieval brewers you might stereotypically expect to a Mittelstand stuffed with specialist technology businesses.

In France, the Henokiens organisation brings together 47 bicentennial family businesses from around the world: they include Ireland’s oldest linen mill, an 18th-century Japanese confectioner, several discreet Swiss private banks, and the Italian gunmaker Beretta (founded in 1526 and with the dubious honour of having supplied arms for every European war since 1650). It awards the annual Leonardo da Vinci prize to those family businesses “that have attained industrialization while transmitting a set of cultural values, traditions, know-how and specific technologies that comprise the intangible and living heritage that is an essential guarantee of [their] continuity”.

Wherever they are in the world, there are commonalities between all of these multi-generational, multi-century businesses – common behaviours that help explain how they’ve managed to survive for so long. In general, successful long-lived businesses:

-

Disregard and deprioritise scale. Scaling and then imploding is failure; success comes from lasting a long time, not getting big while you’re doing it.

-

Focus on a far-off horizon. It’s about passing on the baton to the next generation, which means short-term objectives fade into their correct perspective.

-

Disregard trends and fads. Instead, they focus on long-term, stable shifts and ever-present customer needs.

-

Hoard cash. Perhaps a year or more of operating expenses – which are, in turn, kept as low as possible – in order to weather any storm.

-

Bear the responsibility of inheritance. Who wants to be the one who screwed it all up, the last in the line?

-

Have a sense of higher purpose. They serve something bigger than themselves, most obviously the tradition of the business itself but also their local community or, quite often, a spiritual and ethical tradition.

These are admirable principles, and sound advice for surviving through uncertainty. But most importantly, these businesses must live within the sustainable doughnut. Setting up a business for the long-term gives you an investment – quite literally – in the future. It’s neither possible nor desirable to shirk your impact on the community that you live in and the wider environment: your future success depends on their continuing to flourish. It makes no sense to deplete the natural resources on which your business relies, because you will need those stocks in generations to come – and so the principles of the regenerative economy become even more important.

Shifting our collective focus from the shiny startup to the sustainable, long-lived, multi-generational business won’t be easy. But if businesses tried a little harder to be sustainable, and focused a little more on the long-term, they might just find themselves a little more resilient and a little more long-lived as a result.

Further reading

On doughnut economics:

Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics website

Doughnut Economics, Random House Business, 2018

On Japanese shinise:

Japan’s Oldest Businesses Have Survived for More Than 1,000 Years – So Why are Some of Them Folding Now?, The Atlantic, February 2015

This Japanese shop is 1,020 Years Old. It knows a bit about surviving crises., The New York Times, December 2020

Shinise, Wikipedia

On the German Mittelstand:

Best of German Mittelstand: The World Market Leaders, Florian Langenscheidt, Peter May, Bernd Venohr, Deutsche Standards, 2015.

Add a comment