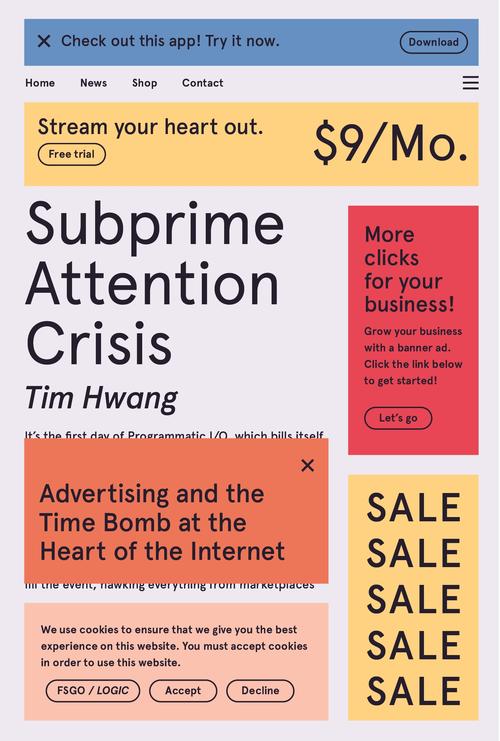

Review: Subprime Attention Crisis

The modern internet is built on the ability of publishers to sell attention and advertisers to buy it – en masse and without human intervention. But what if it’s all bunk?

Perhaps the major innovation of the internet’s last decade has been the rise of programmatic advertising. Powered by an abundance of data gathered by huge platforms like Google and Facebook, this super-targeted, totally automated digital advertising claims to have solved the two thorniest problems in advertising: perfect targeting and perfect attribution.

Rather than targeting people by broad demographies or geographies, you can now target people based on their hobbies and interests, their lifestyle and wealth, the websites they’ve visited, the brands that they like, their geographic location to a frighteningly specific degree, and even the ways in which they’ve behaved on your website or app. And what’s more, all this data allows you to track people through the sales process – online and offline – to actually measure which of your adverts worked. John Wanamaker’s famous quip (“half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half”) has finally been buried.

This is the foundation on which the modern internet is built. Countless small businesses have thrived (the “niche multinationals” among them) with their newfound ability to tightly control their spend, focus only on effective marketing, and reach customers in their particular niches. Newspapers and other publishers, disrupted almost to the point of destruction in the mid-2000s by the moving online of attention and the emergence of social media, have slowly but surely adapted to a world of programmatic advertising, using it both to sell advertising space on their sites and to reach new subscribers of their own. A flourishing world of content creators on platforms like YouTube have emerged, harnessing their huge audiences to attract equally huge incomes from programmatic advertising.

The only problem, Tim Hwang argues in his new book Subprime Attention Crisis, is that these foundations aren’t just unstable: they’re rotten to the core, and in danger of collapse at any minute. And if they go, it’s not just the large advertising platforms that will be destroyed, but the whole edifice of online publishing and commerce.

Observing the current market for programmatic advertising, Hwang sees disturbing parallels with the bubble in the US housing market that ultimately led to the 2008 global financial crisis. In that crisis, Hwang explains, a bubble formed in a fairly routine way, as bubbles have throughout history:

-

First, the market is standardised and financialised. In the case of the US housing market, this involved the creation of “mortgage-backed securities” – tranches of mortgages bundled up and sliced in different ways such that they could be bought, sold, re-sold, and speculated on.

-

Second, the market becomes opaque – by accident or by design. It becomes hard to connect the price of an asset with its underlying value. In the mortgage crisis this involved loans being sliced up into more and more complicated bundles, and worthless subprime loans being given AAA ratings.

-

Next, the real value of the asset declines, but because of the disconnect between price and value, the market doesn’t incorporate this decline into its pricing; the price becomes more and more divorced from reality. In the mortgage crisis, this happened when house prices began to fall throughout 2006 and 2007, in ways that weren’t reflected in the market for mortgage-backed securities and other derivatives until much later.

-

Finally, someone discovers this disparity, the disconnect can exist no longer, the market corrects itself and the bubble bursts. The price suddenly reflects the worthless value of the underlying asset, and someone is left holding the can. In the mortgage crisis, this was when we saw employees of Bear Stearns carrying their possessions out of the office in cardboard boxes.

The world of programmatic advertising, Hwang argues, has followed exactly the same stages of bubble formation and inflation. The market for digital advertising was standardised by the IAB, who defined everything down to the pixel dimensions of ad slots. Huge ad platforms emerged, most notably those of Facebook and Google, who developed highly efficient auction mechanisms that could identify a user, put them into the context of their past behaviour, run an auction to determine a price for their attention at that particular moment, and serve the winning ad to them – all in a matter of milliseconds. Attention itself had effectively been commoditised, able to be bought and sold automatically in tiny slices.

As the programmatic revolution was unleashed, this market for commoditised attention became more and more opaque. Publishers had no idea who was advertising on their sites and in their apps (because every user had a different ad served to them). Advertisers had no idea where their ads were being placed (because they were bidding for the user, and not buying space from the publisher directly). This opacity led to obvious problems of “brand safety”, where makers of wholesome consumer products suddenly found their ads running on white-supremacist, terrorist-sympathising, or pornographic content. But it also led to widespread fraud: click-farms, domain spoofing, bots, all exploiting the opacity of the market in order to generate fake attention, fake clicks – but real profits.

As the market continues to grow, this market opacity makes a bubble possible. But that will only happen if the value of the underlying asset – in this case, users’ attention – declines. Is there any evidence of that happening? Hwang argues persuasively that there is. Ad-blocking is on the rise, on mobile now as well as desktop and particularly in the developing economies. Consumers have advertising fatigue and banner blindness. And they’re clumsy, too; Hwang quotes a study that found that 50% of ad clickthroughs on mobile are the result of accidental “fat finger” clicks. And that’s only thinking about the human users; it’s clear that the value of getting the attention of a script in a click-farm somewhere is less than zero, and yet bots’ share of internet traffic is growing, not shrinking, and click fraud is becoming harder and harder to spot.

Hwang also argues that the value of the medium itself isn’t worth as much as the hype might have you believe. The ability of digital ad platforms to target users is not actually as powerful as urban legends make out. Most data that ad platforms have on most users is inaccurate or incorrect. Ad-buyers have to trust the platforms themselves to report on effectiveness, despite repeated scandals in the past. At least with less-targeted platforms you know their limitations; modern programmatic ad platforms, Hwang argues, offer the greater problem of false certainty.

If these trends continue – the increasing opacity of the market, the declining value of users’ attention, increasing levels of fraud – then the bubble will inevitably burst, and take with it much of the modern internet. Even if you don’t believe that this will happen, and don’t believe that the programmatic advertising market looks like the market for subprime mortgages in 2007–08, the implications of his being right are so stark that they’re worth considering regardless.

For publishers, the situation would be almost intractable. The explosion of independent content creators on YouTube and elsewhere is directly and entirely the result of programmatic advertising. Without the ability to serve ads automatically and en masse to their relatively niche audiences – if every creator had to sell their own media space and cultivate partnerships with advertisers themselves – we wouldn’t have seen anything resembling the landscape we see now. A future without programmatic advertising would be a scary one indeed for many independent publishers and content creators. We got a glimpse of this in 2017, when countless brands pulled their YouTube advertising over concerns about extremist and exploitative content. Smaller content producers suffered the most then, and would suffer the most if the programmatic bubble burst too.

For brand owners – the people who are funnelling money into the system and potentially inflating the bubble – the picture is less stark. Sure, it would turn out that an eye-watering share of their advertising spend – half a trillion dollars of collective spend last year – had been wasted. But, as Wanamaker quipped, waste has always been the norm in advertising. Large brands might be able to dust themselves down, funnel their spend elsewhere, and carry on much as before. Smaller brands, and especially those in the direct-to-consumer space, would find their jobs suddenly much harder, without the budgets to compete for traditional media space.

It’s not all doom and gloom, though – particularly because we’re able to think about this now, before the bubble has burst. Hwang ends with an exhortation to think about what else we could build if we were freed from relying on invasive advertising. Brands should think about the implications of Hwang being right, and think about what that alternative world could look like and what their role in it could be. If what you’re spending on advertising now is effectively wasted, or at least isn’t nearly as beneficial as it claims; if you’re wasting time targeting the wrong people, who are clicking on your ads by mistake; if your conversions are mostly people who would’ve bought anyway… then what’s the risk? What else could you spend your marketing budget on?

That might mean focusing on building your own audiences on the web and on social platforms; buying non-programmatic digital ads, where partner publications are chosen in advance rather than in blind, opaque auctions; supporting content creators through affiliate marketing, sponsorship, and other more transparent and direct mechanics; directing reasonable criticism at the major ad platforms and their effectiveness; and actively working to build a better digital advertising infrastructure, with more accountability and transparency.

Brands have the opportunity to be part of building a different commercial model on the internet, one that doesn’t rely so much on privacy-invading mass data harvesting and that doesn’t concentrate so much power in the hands of a couple of companies. But by voting with their wallets they can do their bit to deflate the subprime attention bubble gently – rather than popping it suddenly.