Creating creative organisations

Efforts to foster creativity in organisations often focus on superficial factors. But what does it mean to create a culture that really produces, filters, and implements new ideas?

Most organisations want to be more creative. Apart from its cultural cachet, creativity is seen as a useful way of coping with the increasing pace of change in an ever-more complex world. But most explorations of how to create creative organisations focus on either the superficial (keep your desk tidy!) or the cargo-culted (adopt your favourite design studio’s five-step process!). Is there anything to be learned from the underlying, ever-relevant dynamics of creativity itself?

The psychologist Donald T. Campbell, writing in 1960, suggested a model of how creative ideas spread. Inspired by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, Campbell proposed three phases in which new ideas and concepts were developed and took root:

- The variation phase, in which new ideas are generated

- The selection phase, in which those ideas are put to the test – the weak ones rejected, the strong ones selected

- The retention phase, in which selected ideas are absorbed by others and integrated into their work

In the messy real world, these phases are not a perfectly demarcated linear process. They’re constantly shifting and overlapping. Quirks of organisations’ cultures, staff, and processes lead to strengths and weaknesses in some areas more than others, too. For example, an organisation might have no trouble coming up with new ideas, producing a constant stream of variations, but then struggle to back the right horse or put ideas into practice. Another might have fantastic collaboration and knowledge-sharing, but struggle to diverge from their existing processes and be bound by inertia.

What does it look like to be effective in all three of these phases? Can individuals optimise their environments for one or all of them? Can organisations create an environment in which all three flourish?

The variation phase

The first crucial phase in the creative process is the variation phase, in which new ideas are suggested. “Variations” are departures from the status quo: changes, new ideas, new processes, new ways of doing things. Without variations, there can be no creativity. Indeed, creativity is often mistakenly thought to involve this stage alone, so focused are we on the “idea generation” aspects of it.

Variations can be intentional variations, the deliberate result of conscious action, or blind variations that are accidental or even unknown.

Blind variations occur constantly and without effort: they’re the inevitable side effect of people going about their daily business, making the occasional mistake and bringing their own idiosyncrasies to their work. In particular, a large source of blind variations is the hiring of new people into an organisation, who bring with them different perspectives and different ways of doing things. These variations can be stamped out or they can be nurtured, but it’s nearly impossible to stop them happening in the first place.

Another hugely important source of blind variations is the actions of competitors and forces outside the organisation. These behaviours change the situation within the organisation in ways that are unclear, unconscious, and unplanned; they force people to react to and contend with a new reality.

Intentional variations, on the other hand, are controlled to a great extent by the prevailing culture. Intentional variations occur when people in an organisation are:

-

empowered – encouraged to take courses of action that they think are appropriate, instead of always following the same processes and having their actions controlled by others

-

encouraged to fail – not punished for deviations that don’t succeed, but rather encouraged to learn and move on

-

explicitly encouraged to innovate – whether as part of their everyday job description, role, and responsibilities or as part of a formal programme of innovation

It’s possible to see these qualities through a single lens: variations flourish in cultures that deliberately dismantle the pressure to conform. Wherever there are humans, there are behavioural norms and a collective pressure to adhere to them. This dynamic exists in all kinds of organisations, but is often strongest in organisations with generally strong cultures – something that’s ordinarily considered a virtue. Businesses strive to have a definite sense of “our way of doing things”, to project a clear idea of their culture to the outside world, to attract employees to a specific way of thinking and set of values – but all of these positive traits also encourage conformity. It’s exactly this pressure from the group to conform, and desire on the part of individuals to conform, that acts to suppress variations. And so organisations that want to be creative must fight against it.

Having a healthy culture of variation is apparent in a number of ways: when employees challenge those further up the hierarchy, bringing forward new ideas and new processes; when processes evolve with changing circumstance, rather than being set in stone, and so don’t break quite so often; when new products or services emerge without prompting or forcing, bubbling up regularly rather than as the result of some sporadic, conscious, top-down innovation programme.

The selection phase

As we’ve seen, blind variation occurs constantly, whether we like it or not. Intentional variation can occur frequently too, especially in healthy organisational cultures that empower individuals and nurture healthy non-conformity. But what happens to those variations once they materialise? Which ones stick, and which ones fade away?

The clearest and most fundamental selection process comes from what the organisation chooses to explicitly and publicly prioritise and incentivise. The overall strategy set by the leaders of the business creates a cascading set of selection criteria that filters throughout the rest of the organisation.

What happens, though, when that selection criteria is wrong? One particularly common way for selection to become unmoored from reality is the so-called competency trap:

“The causes of competency traps are perhaps best understood by considering the two, sometimes opposing, forces that drive a company forward: the ‘exploitation’ of their existing products, and ‘exploration’ of future opportunities. Each will require its own resources and investments… A competency trap occurs when the exploitation arm comes to dominate the company’s workings so that it is no longer structurally ambidextrous.”

This dynamic is the cause of Clayton Christensen’s “Innovator’s Dilemma”, in which a business that listens to customers, uses data, and maximises their margins ends up blindsided by the disruption of a competitor precisely because they were “doing everything right”. This happens because the business’s selection criteria are wrong: they’re selecting for things that look like successes they’ve had in the past, and rejecting things that diverge from that proven pathway to success. That’s a sure-fire way to ignore a promising trend, a new technology, or an underserved customer segment.

A healthy culture of selection is open-minded, freed from the power dynamics of the wider business, and entertains ideas that challenge the status quo. It aligns its internal criteria for selection with the fundamental, environmental criteria of the market, the consumer, and the real world in general. It fights the gravitational pull of “exploitation” and consciously incentivises the easy-to-ignore “exploration” arm.

That means nurturing unconventional innovation and R&D projects, even ones that threaten the business’s cash cows. It means erasing problematic power hierarchies, where institutional power goes to those with past successes – rather than those with future potential. It means exposing ideas to real criteria as soon as possible – the criteria of the customer and the market, rather than internal opinion.

The retention phase

The final phase is perhaps the most important: how effectively are the variations that occur and are selected for incorporated into the behaviours of the organisation? Are the ideas actually implemented, or do they remain mere ideas? Are they built upon and evolved? Is there a feedback loop of further development and collaboration?

In the process of generating variations, conformity is, as we’ve seen, an obstacle. It can introduce a reluctance to deviate from the standard operating procedure. But a strong culture and a closely woven social fabric is essential for retaining and developing ideas further.

So many businesses take this social fabric too far. They have great, collaborative cultures and teams that work fantastically together. As a result, they have much latent potential in the retention phase, but tend to under-perform in the generation of variations – their collaborative culture produces conformity.

Others are the opposite. They’re constantly generating variations, but lack an effective culture to retain and develop them. Sometimes this happens because of a lack of sticking power: the ideas that they generate are flashes in the pan, here today and gone tomorrow. This often happens when a small number of people are disproportionately responsible for generating variations, but the wider culture is either unreceptive to them, unequipped to deal with them, or so focused on the day-to-day that they ignore them.

At other times, it’s because of an organisational inability to shift from a divergent mode of thinking – coming up with new variations – into an implementation mode. Ideas continue to be questioned indefinitely; decisions are never made, because new variations are always offered. A united front is never presented, and the team never works together to implement their ideas.

It’s rare, then, to find organisations that excel at all three phases of creative ideation and implementation. The main reason for that is that they are in some respects directly incompatible. The behaviours that encourage variation – divergent thinking, a disrespect for authority and conventional wisdom – can become obstacles to selection and retention. The behaviours that enhance retention – collaboration and knowledge-sharing – tend to encourage group-think and conformity, and thereby reduce the quantity of variations.

The ideal answer is to create a multi-modal organisation: one capable of thinking and behaving in different modes at different times. That means creating not just an extraordinarily flexible organisation, but one that has a level of self-awareness and perspective that’s rare to find – able to determine what situation it’s in and adopt different behaviours accordingly. But that’s not as easy as it sounds, and perhaps represents a far-off target more than a roadmap for change.

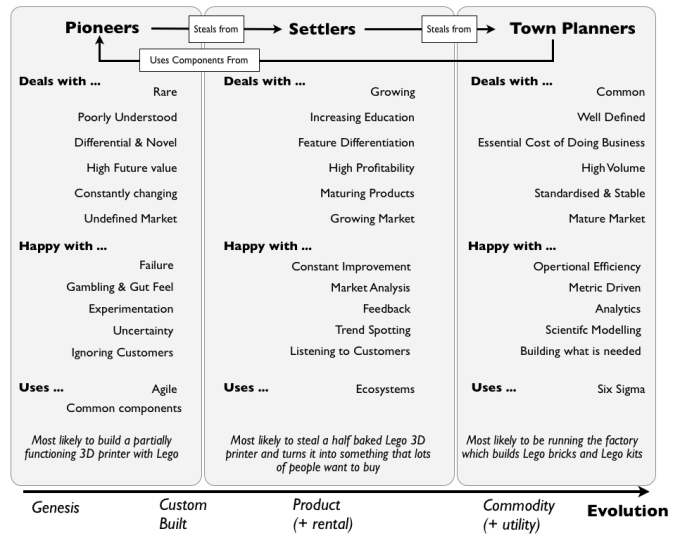

Looking at technology businesses, Simon Wardley has described such multi-modal organisations with his “Pioneers, Settlers, and Town Planners” model of aptitudes:

(Image: Simon Wardley, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Pioneers are those who excel at variation, who are totally unconstrained by the status quo and who come up with ideas that fail more often than they succeed. Settlers are fantastic at selection, choosing which of the pioneers’ crazy ideas to develop further. And Town Planners are brilliant at seeding new ideas into the broadest possible culture, smoothing out any rough edges and accelerating the pace of change to an industrial scale.

Organisations that fail at one of the three phases of the creative process often do so because they fail to recruit or fail to recognise people across these three aptitudes. Their internal culture is only capable of functioning in a single mode; every problem is treated as one to be solved by the mode of thinking that the organisation finds most comfortable, whether that’s coming up with endless new ideas or vigorously doubling-down on the ones they have. Finding ways to incorporate other aptitudes and other ways of behaving into your culture might just be the key to unlocking the creative process.

Further reading

D. T. Campbell. “Blind variation and selective retention in creative thought as in other knowledge processes”. Psychological Review 67:380-40067:380-400, November 1960

Dean Keith Simonton. “Creative thought as blind-variation and selective-retention: Combinatorial models of exceptional creativity”. Physics of Life Reviews 7:2:156–179, June 2010

“Evolutionary Epistemology”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, January 2020

Howard E. Aldrich and Martin Ruef. “Organisations Evolving”. SAGE Publications, 2006

Seth Kaplan, Luke Brooks-Shesler, Eden B. King and Steve Zaccaro. “Thinking inside the box: how conformity promotes creativity and innovation”. “Creativity in Groups”, pp. 229–266. Emerald Books, 2009

David Robson. “How to avoid the ‘competency trap’”. BBC Worklife, June 2020

Clayton Christensen. “The Innovator’s Dilemma”. Harvard Business Review Press, 2016.

Simon Wardley. “On Pioneers, Settlers, Town Planners and Theft”. March 2015

Add a comment