Machinery hurtful to commonality

Luddites, technology and “content”

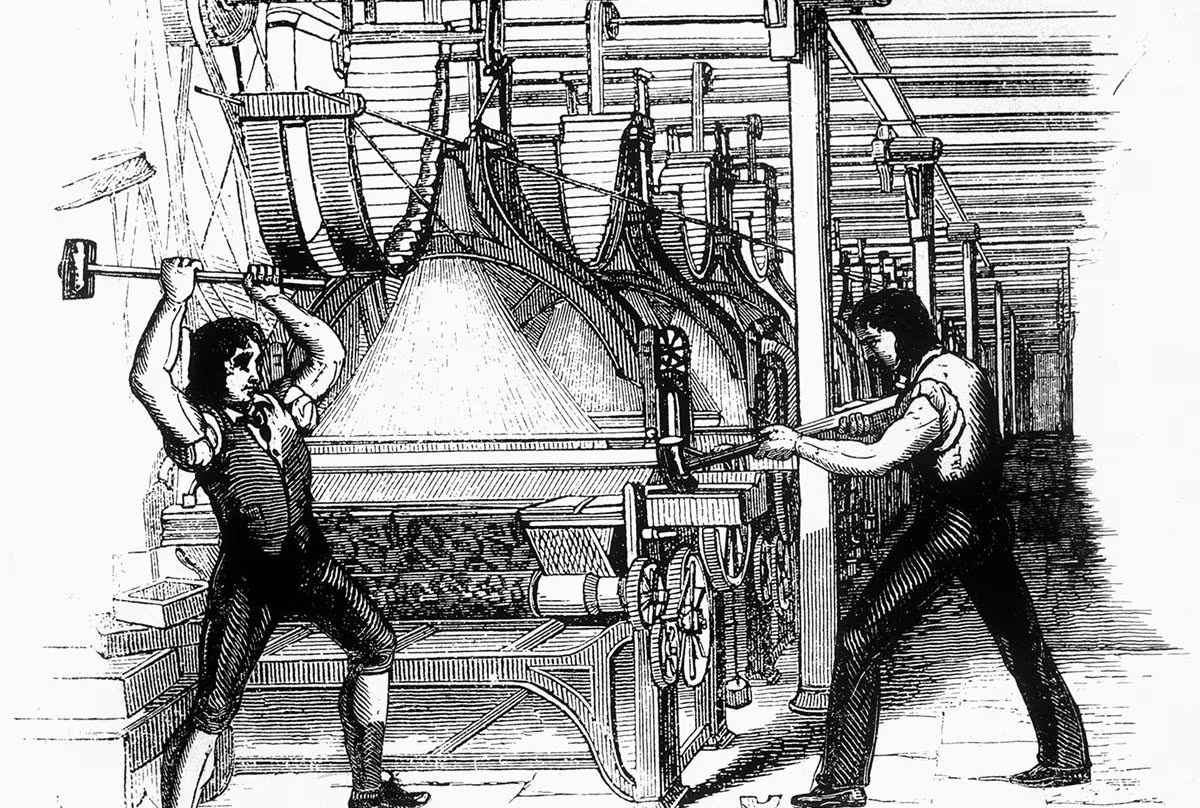

In the midst of the industrial revolution, an organised movement in the East Midlands of England challenged the mechanisation of the textile industry by smashing the machines that were replacing and devaluing their labour. They were the Luddites, named for their mythical leader Ned Ludd. Since then, the word “Luddite” has come to mean a sort of slack-jawed bumpkin, terrified of progress and ignorantly standing in the way of modernity.

That’s a bit harsh on the Luddites, though. They didn’t challenge the very existence of machines. They didn’t oppose all progress. They weren’t trying to preserve some Arcadian craftsman’s idyll at the expense of technological advancement. The Luddites were in fact skilful operators of machinery, and their opposition was not to the machines but to their unfair use, to the capital that was embodied within them, and to the factory owners who wielded that capital against them.

The Luddites weren’t demanding the destruction of all machinery and the banning of automation. They wanted machines to be operated by workers who had undergone an apprenticeship and who were paid well, and they wanted them to be used to produce high-quality – rather than high-margin – goods. They demanded the return to a system, challenged by the industrial revolution, in which it was possible to make a good living as a skilled manufacturer. In their own words, they fought against “all machinery hurtful to commonality”.

It used to be possible to make a good living as a jobbing musician; in the era of pitiful streaming revenues, AI-generated slop and muzak on Spotify, it no longer is. It used to be possible to make a good living as an ordinary, non-A-list screenwriter or film crew; in the era of collapsing streaming budgets and the elimination of residuals, it no longer is. It used to be possible to make a good living writing for a niche audience on the web, funded by either advertising or membership fees; in the era of ad fraud and subscription fatigue, it no longer is.

We’re all just making algorithmic dogfood for the content factory:

“We subsidize our YouTube documentaries with Amazon links for dildos and run a tarot card Instagram! Our tech review site is only financially solvent because we have an HBO show no one watches! We own an Eastern European Facebook page network that focuses on classic cars and algorithmically-generated DIY hacks that don’t actually work which distributes a podcast we produce with Trisha Paytas!”

Call it “content”, or “media”, or whatever you like; the business model of it looks to be pretty screwed up, and the coming of AI is only accelerating that.

The Luddites had style. They understood communications and public relations instinctively, taunting the authorities with public letters from “General” Ned Ludd and winning more converts to their cause. They had swagger, too. They agitated for an economic system in which the sturdy self-reliance of the working classes was the dominant force, not the inhuman insensitivity of the market, and they were prepared to use violence to forge that system. It’s no wonder they spooked the forces of capital and the state.

Their problem was that, while they might have had right on their side, they lacked sufficient might. The power they challenged wasn’t simply economic; it controlled physical force, too. Factory owners hired private militias; the state, scared by the apparent threat to the existing order, sent the army in to crush the Luddites when they protested, and punished them afterwards in the courts. The Luddites lost, in the end.

They lost because the new technologies of the time either reinforced existing power structures or created new ones that were equally unjust. New elites had emerged to challenge the old. It was now the factory owner, rather than the landed aristocrat, but power remained just as concentrated – it was just concentrated in a different place.

The disruption of which Silicon Valley is so fond has resulted in the same dynamic in our own time. Power has been clawed away from film studios and newspapers, but it’s even more concentrated in the hands of technology companies. This focus of capital in entities that are backed by venture capital or publicly traded has led to a state of constant and exhausting enshittification.

One of the most important lessons in business is that, as Steve Blank said, “the minute you take money from someone else, their business model becomes your business model.” The venture model is to invest in businesses that can blow up, in both senses of that phrase – so either to fail fast, or to grow spectacularly large. And so taking venture funding makes one of those two outcomes inevitable. The public markets are about shareholder primacy and steady-but-infinite growth. And so going public binds your future decision-making to the short-termist whims and demands of the market.

Businesses with either of these ownership models are by their very nature incentivised to create a world in which capital can be substituted for labour, in which the role of the individual human is marginalised, whether or not the people within those businesses are conscious of or desirous of it. Those ownership models are structurally guaranteed to produce something profitable to shareholders, but “hurtful to commonality”.

The problem is not the technology itself, which in any case can’t be uninvented. The problem is the systems of power it is borne out of and that it helps to perpetuate. How can we change the incentives?

Hollywood studio bosses in the 1930s and 1940s were hardly staunch socialists. Media power then was concentrated in a small number of companies owned by fantastically rich men. And yet from that era and that ownership structure we ended up with the residuals model, a form of profit sharing that allowed creatives to profit from runs and re-runs and overseas transmissions of their work.

That system came about through the work of strong labour unions, but the strength of those unions was only possible because even the most narrow-minded of suits understood the essential role of labour in the creation of films and TV shows and were incentivised to keep them at least moderately happy. Even now, Hollywood unions wield great power and can bring large companies to the table. Creatives controlled the means of production in a way that factory workers never did, and in the past they used that power to their advantage.

The modern problem, though, is that the power is no longer in production. It’s in distribution, and in the aggregation of attention. And the platforms that aggregate that attention are controlled exclusively by venture-backed technology businesses.

But the lesson of Netflix and Amazon Prime and Instagram and TikTok is that attention goes to where the content is. The pipes the content flow down are largely undifferentiated. People’s loyalty is to what they watch, not the service on which they watch it. There isn’t much lock-in here. That was what harmed traditional studios, but it has the power to harm the streamers, too.

And the lesson of a third of the UK population watching Gavin & Stacey over Christmas is that there’s still demand for content more ambitious than cat videos and fail compilations. If Spotify insists on shovelling more royalty-free muzak at people, if the quality of programmes on Netflix declines, that creates an opportunity elsewhere.

Enshittified tech platforms shouldn’t be able to command attention forever. Their own lust for growth should be the start of their downfall. It should be possible to compete with them, to build something more compelling. There are no hard technical problems to solve here, there is nothing that requires hordes of programmers and squillions of dollars of seed funding, and so nothing that requires the venture capital deal with the devil.

Luddism feels like a franchise in need of a reboot. And why not? Why can’t we have a sort of guild socialism in the world of media? Why can’t the workers own their work and bring it directly to the public? Why can’t creatives control distribution? What would stop a cooperative streaming platform, run for the benefit of its members, funding ambitious projects, charging people money to consume them, and distributing the surplus to the creators?

I think it’s high time we rehabilitated the term “Luddite”, and created some machinery beneficial to commonality.

Add a comment