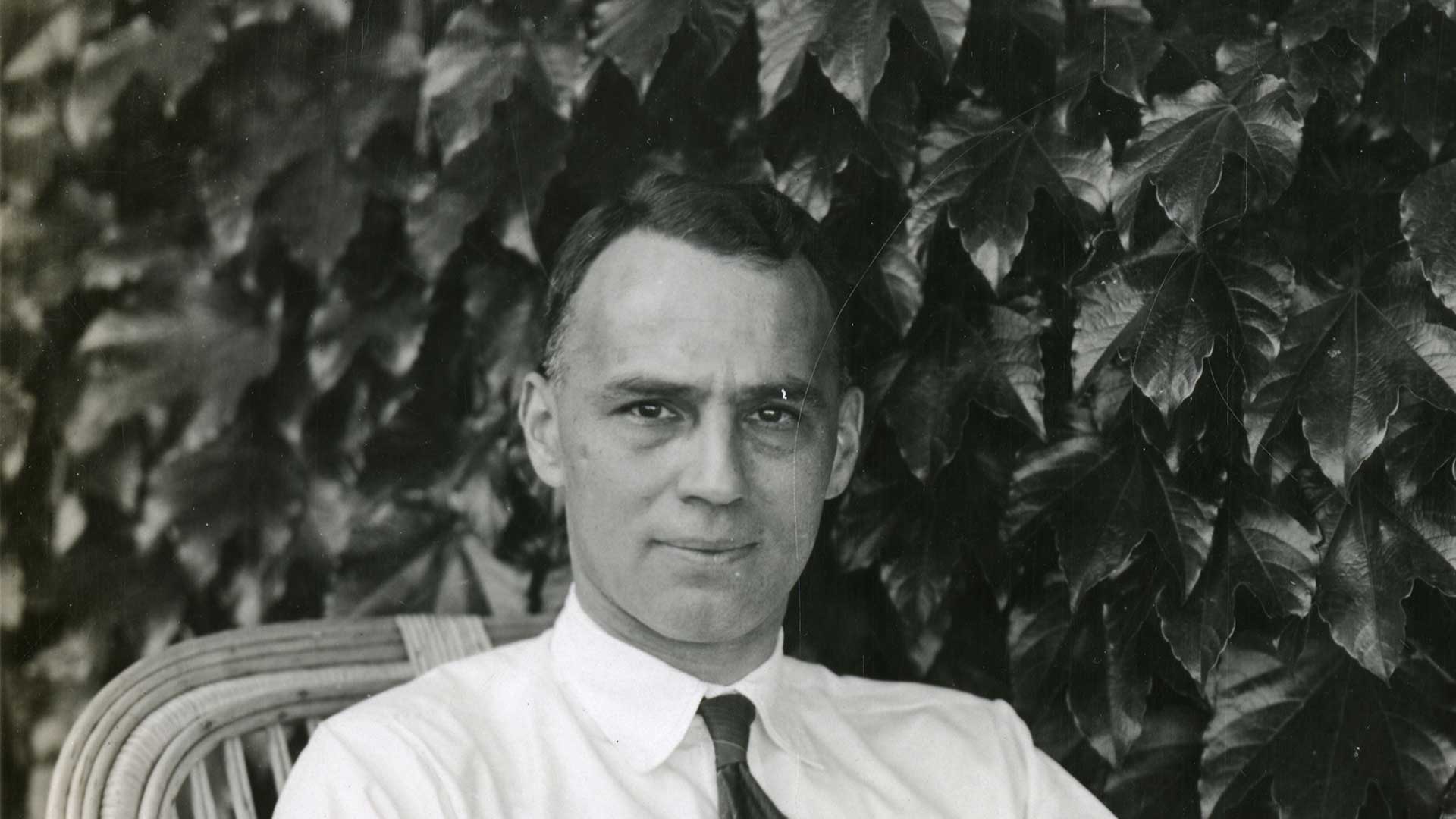

The anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson, who died in January, is the

subject of a fantastic retrospective in Edge that features many of the

things she wrote and contributed to the publication over the years.

If you read only one thing, make it “How to be a Systems

Thinker”, from 2018. It’s a goldmine of

thoughtful advice about thinking, from the interconnectedness of complex

systems:

“We were doing all sorts of things to the planet we live on without

recognizing what the side effects would be and the interactions… Once

you begin to understand the nature of side effects, you ask

a different set of questions before you make decisions and projections

and analyze what’s going to happen.

“We have taller smoke stacks on factories now, trying to prevent smog

and acid rain. What we’re getting is that the fumes are traveling

further, higher up, and still coming down in the form of acid rain.

Let’s look at that. Someone has tried to solve a problem, which they

did – they reduced smog. But we still put smoke up the chimney and think

it disappears. It isn’t gone. It’s gone somewhere. We need to look at

the entire system. What happens to the smoke? What happens to the

wash-off of fertilizer into brooks and streams? In that sense, we’re

using the technology to correct a problem without understanding the

epistemology of the problem. The problem is connected to a larger

system, and it’s not solved by the quick fix.”

…to the importance of narrative and metaphor in our thinking:

“It turns out that the Greek religious system is a way of translating

what you know about your sisters, and your cousins, and your aunts

into knowledge about what’s happening to the weather, the climate, the

crops, and international relations, all sorts of things. A metaphor is

always a framework for thinking, using knowledge of this to think

about that. Religion is an adaptive tool, among other things. It is

a form of analogic thinking.”

…and so much more besides.

She wraps it up with an exhortation not to neglect bigger-picture

thinking:

“The tragedy of the cybernetic revolution, which had two phases, the

computer science side and the systems theory side, has been the

neglect of the systems theory side of it. We chose marketable gadgets

in preference to a deeper understanding of the world we live in.”

#