Hello everyone,

I’ve been enjoying BlueSky in the last few months, as a refreshing alternative to the burning cesspit that is X. One of the pleasing accidents of building up a following list from scratch on a new platform is that you end up following more people in the groups that have moved over in greater numbers, and so I’ve found my feed skewing much more towards comedians and writers than tech folks or whoever else I was following on Twitter.

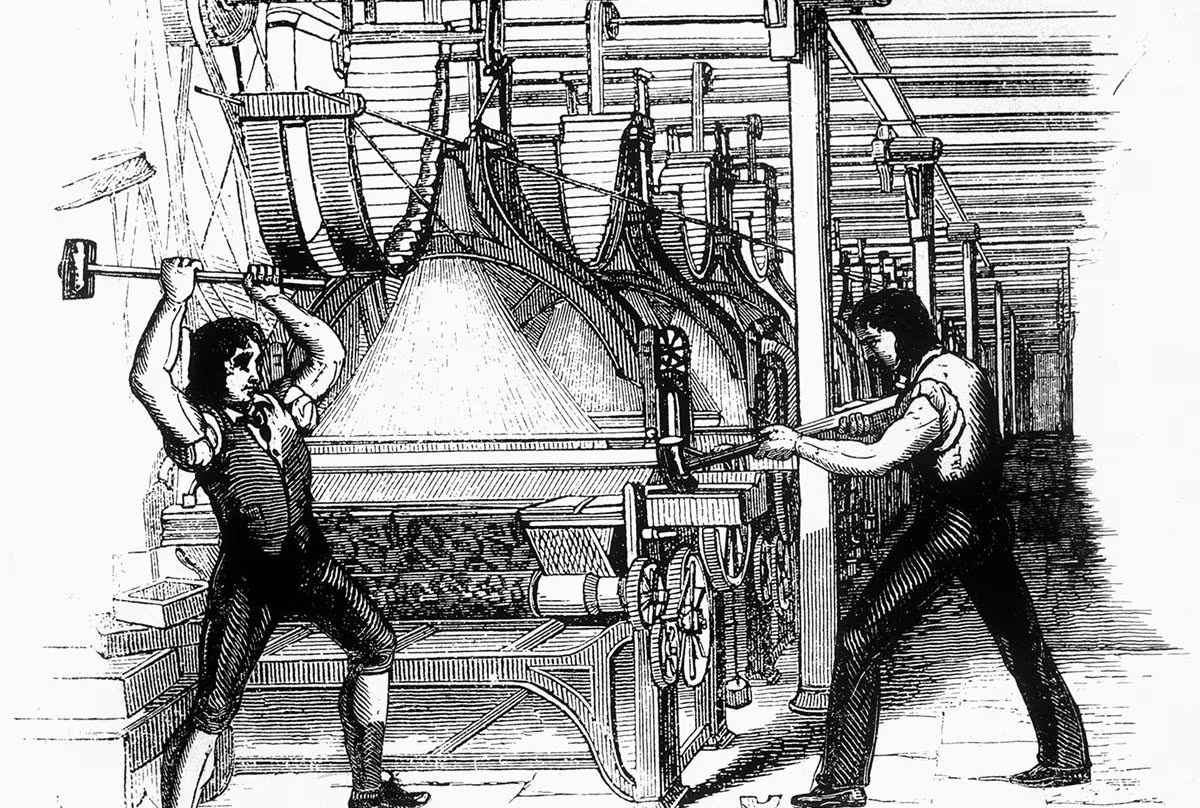

A recurring theme among them is rage against the current status quo of streaming platforms, tech companies and the advent of AI. This new Luddite movement, standing against the nature of technological development, is pretty compelling; this week’s article digs into how it could be more successful than the first Luddites were.

Hope you enjoy,

Rob

This week’s article

Machinery hurtful to commonality

A new generation of Luddites stand against the big streaming platforms and AI companies. What happens next?

Click here to read the article »

Since it’s been so long since my last email, you’ve got a bumper crop of links too:

This week’s 12 interesting links

How to solve the £100m bat tunnel problem

The UK has been attempting to build a high-speed railway line called HS2 for years. Its development has been dogged by all sorts of problems, but perhaps the most farcical was the revelation that it had spent £100m on a 1km long tunnel for bats, in an area that was home to around 300 bats – an insane £300k per bat.

In this great post, Sam Dumitriu talks about why decisions like that get made, but also digs into some of the planning changes the government have made to hopefully make them less likely to happen in the future.

The plans seem to be better both from a “getting stuff built” perspective and a “preserving nature” perspective, which seems like a rare win. But it’s not over the line yet; it needs legislation to pass, which means getting it past lobby groups that are invested in the status quo.

“Wasteful spending on fish discos and bat tunnels should infuriate everyone whether their priority is world-class infrastructure or protecting endangered species. By fixing the Habs Regs, we can cut the cost of building new clean infrastructure and go beyond preserving the nature we have to actually enhancing and restoring it.”

Sophie Smith on the Pelicot trial

One of the most powerful things I’ve read in ages: Sophie Smith on Gisèle Pelicot and what her experience tells us about humanity, and men, and complicity.

“What are we taught not to see? What do we see and are taught not to talk about? If we want to understand the logics of a ‘rape culture’ that produces the ‘Monster of Avignon’, the scores of men he convinced to join him, the website on which they all met, the terms in which they made their excuses, the porn they and millions of others consume, the desire that this porn both writes and represents, the desire of men to get from women what they know they don’t want to give, the getting it because they can, the fantasy that the women they took it from wanted it anyway, the women who are taught to stay quiet, who are kept quiet, and the ones who are ignored, defamed or humiliated when they do not – if we want to understand this ‘culture’ (or rather, this way that we distribute power) might we need to think not about the ‘monsters’, but about the gruff, decent guys, the guys we love and forgive, the guys who are ‘not like that’, for whom we silence small anxieties about coercion and hurt and trust precisely because we are so relieved they are not monsters? And perhaps also because we are worried that if we do speak up they might leave us, exclude us, react with the infantile fury we are taught so carefully to contain? Are we not, when we look closely, surrounded by these small acts of accommodation, denial, repression, evasion?”

Dan Davies on farming and inheritance tax

The streets of London were crawling with tractors recently, protesting the changes to inheritance tax on farms. (Previously farms were exempt from inheritance tax; now farms worth over £1m will be subject to it.)

My initial response was to buy the line that this would only affect a tiny minority of farms, and that it was shutting a pretty egregious tax loophole exploited by the likes of James Dyson and Jeremy Clarkson.

It has felt impossible to find a nuanced view because of the strength of feeling on both sides. But in this article Dan Davies thoughtfully explains the economics of it, and why my gut feeling was actually wrong:

“In the thirty or so years since Agricultural Land Relief was brought into the tax code, the price per acre of farmland has gone up roughly fourfold, and according to credible numbers I’ve seen, there are plenty of farms which, considered as businesses, are earning a return on assets of less than 1% (£35,000 of annual profit on a farm valued at £3m is apparently pretty good going).

“In that sort of situation, you have to value the tax shield separately – what the yeopersons of Olde Englande actually own might be a farm worth about £700,000, with a mortgage on it, and a £2.3m tax asset. So if the tax position changes, the value of the farm should be expected to plummet, and they go from being asset-rich—cash-poor to just poor.

“And this matters a lot… The asset value of a family farm, although it’s for the most part not realised or consumable wealth, is potentially a big part of the contingency reserve of that family against uncertainty. If things get really bad, either in a business context or some other family emergency, you can borrow against the value of the land or, in extremis, sell off a few acres.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty in farming! If the backstop of being able to sell bits of tax-advantaged assets isn’t there, then rather than being gradually eroded over four or five generations (which seemed like the natural outlook for the small farm sector), you’re likely to see lots of them wiped out suddenly in the next drought or foot & mouth disease outbreak.”

Cabel Sasser on Wes Cook

I suspect this will do the rounds, as it thoroughly deserves to. Try to watch it without spoilers. It’s Cabel Sasser’s talk from XOXO this year, it’s about art and memory and what lives on of us after we pass, and it’s lovely. #

Why “paradigm” and “paradigmatic” are pronounced differently

I’ve always wondered why “paradigm” is pronounced pa-ra-dime, but “paradigmatic” is pronounced pa-ra-dig-ma-tic. Why does that silent ‹g› suddenly become noisy?

This answer, from the user tchrist on the English Stack Exchange, explains it incredibly clearly.

In short: the ‹g› is there because it’s there in the Greek original. We can’t pronounce it because English phonotactics forbid the pronunciation of a /g/ followed by a nasal at the end of a word (hence “align”, “consign”, “foreign”, “phlegm”, etc.). But keeping the ‹g›, rather than spelling it “paradim” or “paradime”, is helpful:

“We tend to keep the written ‹g› in English words like this, even though we ‘can’t’ say it there at the end of the word right before that final nasal. This helps us understand the shared relationship with longer words like paradigmatic that have a vowel after the nasal, which allows the /g/ to ‘reappear’. But we probably no more ever said it in paradigm(e) than we ever said it in phlegm. Our phonotactic rules forbid it.”

King’s Cross, a miracle in London

The Economist with a gushing tour of the newly redeveloped King’s Cross:

“Some complain that this sleek King’s Cross is a betrayal of its grotty past. Far better to see the district as a sign of a city building its future. If a resurgent Britain finds itself at a technological frontier, it will be thanks to the likes of DeepMind plying their trade in the place where prostitutes once did theirs. If Britain is only to maintain its current trajectory of relative decline, then the success of King’s Cross is still necessary: selling off Victorian gasworks and charging foreign students £28,570 per year in tuition fees is a good living.”

It brought to mind Nik Cohn’s excellent Yes We Have No, a 1998 travelogue around what he called “the republic”; the rag-tag social underbelly of travellers, freaks, hippies, new-age druids, Elvis impersonators, and others that had opted out of the British mainstream. It centres on King’s Cross in its 1990s guise, before everything that the Economist gets so excited about, when it was home to squats and delapidation but also a thriving counterculture. Two competing visions of a world; one that won, and one that lost. #

The 3 AI use cases: Gods, Interns, and Cogs

I wrote earlier this year about potential use-cases for AI, including things like “the rubber duck” and “the tireless intern”. In this post, Drew Breunig outlines three much clearer and more tangible categories of use-case: Gods (superintelligences that can replace humans and act autonomously), Interns (copilots that work under close human supervision), and Cogs (small, self-contained, automated functions that operate as part of a larger process). It’s a great classification. #

You don’t need words to think

This interview with Evelina Fedorenko of MIT is fascinating. She began her scientific career with an assumption, shared by many people, that language is somehow fundamental to cognition; that both language and cognition were both uniquely human abilities, and that each underpinned the other.

It’s a common – and fairly understandable – assumption. (She explains some of the reasons why it’s so intuitive in this article). In particular, most people have relatively strong inner speech – a sensation of a “voice inside our heads” that seems to enable us to think things through. That leads us to imagine that it’s this inner voice that is our thinking process.

But, as Federenko explains, it’s simply not true. There is likely to be some sort of underlying “language of thought” in our brains, but it’s not the same as natural language. Both humans with linguistic impairments and animals – who obviously lack language entirely – are capable of cognition. And Federenko also conducted experiments on people with no such impairments, checking with parts of the brain were active during cognition tasks:

“So you can come into the lab, and I can put you in the scanner, find your language regions by asking you to perform a short task that takes a few minutes – and then I can ask you to do some logic puzzles or sudoku or some complex working memory tasks or planning and decision-making. And then I can ask whether the regions that we know process language are working when you’re engaging in these other kinds of tasks. … We find time and again that the language regions are basically silent when people engage in these thinking activities.”

Language, then, is just one of several things that make us humans what we are:

“It’s most likely that what makes us human is not one ‘golden ticket’, as some call it. It’s not one thing that happened; it’s more likely that a whole bunch of systems got more sophisticated, taking up larger chunks of cortex and allowing for more complex thoughts and behaviors.”

Against lists of books

I meant to link to this earlier this year, but just stumbled upon it again in an open tab (yes, from August, so shoot me) and remembered how good it was. Sam Kriss takes on the now-ubiquitous “book lists”, taking aim first at the middlebrow blandness of Barack Obama’s, then the angsty teenage boydom of Reddit’s:

“What we’re looking at isn’t really a list of the greatest books ever written, it’s a bunch of examples of one very particular type of book: the long, morose psycho-philosophical novel. Like every list of books, it’s an exercise in summoning an aspirational type. This time, it’s the brilliant sensitive young man, quiet, maybe lonely, misunderstood, a creature with hidden depths. The long, morose psycho-philosophical novel is what this type of person is supposed to read.”

It’s hard to argue with his prescription:

“I’m sick of lists of books. Reading lists, top tens, flowcharts, curriculums, canons, counter-canons, the lot. Pathetic activity. Someone could write out the name of every single book I really love, ranked impeccably, with no omissions and no interpolations, and I’d spit cold venom in their face. I think the only way to read with dignity is to read organically, genealogically, backwards, by touch. Not running down a list, but excavating, following the seams where words bleed into each other.”

Foundations: why the UK economy is stagnating

It’s difficult to argue with this article’s damning assessment of Britain’s inability to build just about anything, and the economic stagnation that has resulted:

“Real wage growth has been flat for 16 years. Average weekly wages are only 0.8 percent higher today than their previous peak in 2008. Annual real wages are 6.9 percent lower for the median full-time worker today than they were in 2008. This essay argues that Britain’s economy has stagnated for a fundamentally simple reason: because it has banned the investment in housing, transport and energy that it most vitally needs. Britain has denied its economy the foundations it needs to grow on.”

I’m not sure I agree with the libertarian “just remove the red tape” prescription at the end of it; I think the authors’ policy recommendations are undermined by the example they themselves use, France, which is hardly some Thatcherite paradise of unfettered market forces. But perhaps it’s churlish to split ideological hairs on solutions: the problems seem so vast that scarcely anything could be worse. #

The collapse of self-worth in the digital age

Publishing, like virtually every other industry, has attuned itself to the ocean of data that now exists, using it to measure the worth of art and artists in real-time. From Thea Lim:

“Only twenty years ago, there was no public, complete data on book sales. Until the introduction of BookScan in the late ’90s, you just had to take an agent’s word for it. ‘The track record of an author was a contestable variable that was known to some, surmised by others, and always subject to exaggeration in the interests of inflating value,’ says John B. Thompson in Merchants of Culture, his ethnography of contemporary publishing.

“This is hard to imagine, now that we are inundated with cold, beautiful stats, some publicized by trade publications or broadcast by authors themselves on all socials. How many publishers bid? How big is the print run? How many stops on the tour? How many reviews on Goodreads? How many mentions on Bookstagram, BookTok? How many bloggers on the blog tour? How exponential is the growth in follower count? Preorders? How many printings? How many languages in translation? How many views on the unboxing? How many mentions on most-anticipated lists?”

Lim’s heartfelt piece explains powerfully what that culture of measurement does to an artist – and what it’s doing to all of us.

“We are not giving away our value, as a puritanical grandparent might scold; we are giving away our facility to value. We’ve been cored like apples, a dependency created, hooked on the public internet to tell us the worth.”

Why does Ozempic cure all diseases?

Over at Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander digs into the science behind anti-obesity drug Ozempic, and the subsequent array of secondary effects that have emerged in the scientific literature.

“GLP-1 receptor agonist medications like Ozempic are already FDA-approved to treat diabetes and obesity. But an increasing body of research finds they’re also effective against stroke, heart disease, kidney disease, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, alcoholism, and drug addiction.

“There’s a pattern in fake scammy alternative medicine. People get excited about some new herb. They invent a laundry list of effects: it improves heart health, softens menopause, increases energy, deepens sleep, clears up your skin. This is how you know it’s a fraud. Real medicine works by mimicking natural biochemical signals. Why would you have a signal for ‘have low energy, bad sleep, nasty menopause, poor heart health, and ugly skin’? Why would all the herb’s side effects be other good things? Real medications usually shift a system along a tradeoff curve; if they hit more than one system, the extras usually just produce side effects. If you’re lucky, you can pick out a subset of patients for whom the intended effect is more beneficial than the side effects are bad. That’s how real medicine works.

“But GLP-1 drugs are starting to feel more like the magic herb. Why?”