Hello everyone. This week’s article is about trying to keep things simple, and why our unconscious makes that harder than you might expect.

There are also some interesting links, covering everything from the state of criminal law in the UK to developments in AI-enhanced creativity.

Enjoy! (And, as ever, if you think you know someone who might enjoy this email, please do forward it on.)

Have a lovely week,

Rob

This week’s article

The simplicity of subtraction

Even though we’re surrounded by encouragement to keep things simple, we find it hard not to add “just one more thing”

We’re all familiar with the adage “less is more”. People love to quote Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who said that “perfection is achieved not when there is nothing more to add but when there is nothing left to take away.” We reserve museum space for the work of Dieter Rams and Jony Ive, praising the sleek simplicity of their designs. Rams’s entire approach was summed up as “less, but better”. “The ultimate sophistication,” said the art critic Leonard Thiessen, “is simplicity.”

Why do we need to remind ourselves quite so often that adding things isn’t always the answer – so often that it becomes a bit of a cliché? Why is simplicity not our natural inclination?

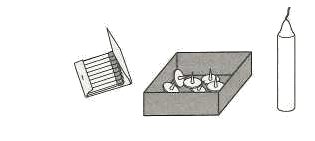

In the 1940s Karl Duncker conducted a simple psychological test. He gave participants a book of matches, a box of thumbtacks, and a candle, and instructed them to fix the candle to a cork board and then light it in a way that prevented wax from dripping onto the table below.

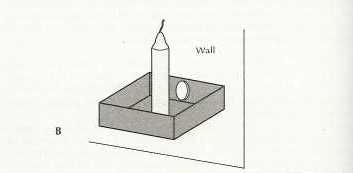

Some participants tried to stick the candle to the board using the thumbtacks directly, pinning them through the wax. Some more creative participants lit the candle, melted some wax, and used that to stick the candle to the board. What few did, though, is the easiest solution: to tack the box to the board, then simply stand the candle up in the box.

This is a result of “functional fixedness”. Because the box was introduced to the participants as a means of storing thumbtacks, it was difficult for them to see it any other way, and particularly not as a sort of ersatz shelf. Its function was fixed in their minds. If, however, you repeat the test and supply the participants with the tacks and box separately, they’re far more likely to see the “correct” solution. The box’s function is no longer fixed.

Our disinclination to pursue simple solutions has a similar root. A study last year revealed that, when solving problems, we’re less likely to see solutions that involve taking something away than we are ones that add something new. We have “additive fixedness”: we instinctively look for additive solutions and are blinded to subtractive ones, just like we’re blinded to using the box of tacks as a shelf.

You see this effect in so many areas, but it’s particularly prevalent in the creative world. When asked for their view on creative work, those untrained in the art of critique are more likely to suggest adding something than taking it away. In doing so, the work gets that little bit more complex – and, most likely, that little bit less good.

Not only are we less likely to see solutions that involve subtraction, even if we do see them we’re less likely to pursue them. That’s true for social reasons: if we’re taking away something that someone else built or put effort into, that might not be received well by them. We’re also conditioned to see creative efforts as more worthwhile than destructive ones; more people aspire to be the film director or author or chef than to be the critic who tears down their work. And finally, there’s the good old sunk costs fallacy, whereby we’re reluctant to abandon something that we’ve already begun to put effort into.

So, while quotes about “less is more” might be so commonplace as to be clichéd, they’re serving a useful job. We simply do need to be told this, over and over again. Unless we shock ourselves out of our default behaviour, we’re unlikely to take the route of removal but instead will tend to load things up with more complexity.

Click here to read the article »

This week’s five interesting links

The DALL·E 2 prompt book

Part of the skill of augmented creativity will be writing good prompts for the AI to follow. With that in mind, Guy Parsons of DALL•Ery GALL•Ery showcases some interesting examples, and offers advice about what seems to work and how.

One of the most interesting sections is on the ethical quandaries thrown up by DALL•E’s ability to replicate the styles of individual artists:

“Artists need to make a living. After all, it’s only through the creation of human art to date DALL•E has anything to be trained on! So what becomes of an artist, once civilians like you and I can just conjure up art ‘in the style of [artist]’?

Van Gogh’s ghost can surely cope with such indignities – but living artists might feel differently about having their unique style automagically cloned.”

There are no easy answers, morally or legally. #

Attrition – Joanna Hardy-Susskind

A difficult read from criminal barrister Joanna Hardy-Susskind, explaining just how nightmarish conditions at the criminal bar have become (hence the recent strikes):

“The finances have never kept pace with the fight. With what is required of me. With what is required of the mass of legally-aided barristers who ultimately have to rely on successful partners, generous families or sheer luck to get by. But, money aside, it is the conditions that deliver the sucker punch. Without a HR department the job takes and takes. There is no yearly appraisal. No occupational health appointment. No intervention. No one to assess the toll. There is a high price to be paid for seeing photos of corpses, for hearing the stories of abused children and for sitting in a windowless cell looking evil in the eye. There are no limits as to how much or how often you can wreck your well-being, your family life, your boundaries. No limit to how many blows the system will strike to your softness. The holidays you will miss, the occasions you will skip, the people you will let down. The thing about words is that they sometimes fail you. When you emerge from a 70-hour week and notice the look in the eyes of the proud parents who propelled you here – but miss you now.”

Inside the far right’s growing obsession with art

Twitter is awash with “traditionalist” art accounts that profess a yearning for simpler times. They mostly feature figurative paintings, architecture from the gothic to the baroque, lots of Greco-Roman sculpture and, of course, lots of white people.

James Greig argues that this isn’t just philistinism; it’s part of a broader sweep of far-right propaganda, rooted in our current politics:

“By comparing modern art with conventional depictions of rural scenes and able-bodied white people, this digital subculture is expressing a specific hierarchy of values. It’s about returning to a lost halcyon age of (implicitly white) western civilisation, which is sometimes Ancient Greece, sometimes the Renaissance, and sometimes Mad Men. It expresses a desire to return to ‘the natural order of things’, which has been degraded by modernity and multiculturalism, and conceptualises beauty as something which is eternal and objective.”

Explain Jargon

Another great usage of GPT-3, like I’ve written about before. This time, it’s for jargon-busting: insert any text, from any field, and it will translate things into plain English.

For example, this:

“The three-dimensional structure of DNA – the double helix – arises from the chemical and structural features of its two polynucleotide chains.”

…becomes:

“The shape of DNA is called a double helix, and it forms due to the chemical makeup and structural characteristics of the two different strings of molecules that make up DNA.”

Pretty interesting. #

Stewart Brand’s Dubious Futurism

I’ve always admired Stewart Brand, without necessarily ever having dug deep into his story. He’s one of those unavoidable characters who pop up at every historical juncture, influencing everyone from hippie LSD trippers to titans of industry in Silicon Valley.

My vision of him as a benign sage is certainly at odds with this brilliant profile – or perhaps hatchet job – by Malcolm Harris in The Nation, which paints Brand as a cynical huckster, driven by individualistic greed to sell whatever people were buying and working with anyone who’d pay him:

“Stewart Brand is not a scientist. He’s not an artist, an engineer, or a programmer. Nor is he much of a writer or editor, though as the creator of the Whole Earth Catalog, that’s what he’s best known for. Brand, 83, is a huckster – one of the great hucksters in a time and place full of them. Over the course of his long life, Brand’s salesmanship has been so outstanding that scholars of the American 20th century have secured his place as a historical figure, picking out the blond son of Stanford from among his peers and seating him with inventors, activists, and politicians at the table of men to be remembered. But remembered for what, exactly?”