Six years after Brexit, well over two years into Covid, it still feels like everything is a bit… broken. Supply chains, public services, and businesses all feel at breaking point, with nothing more to give, being asked continually to do more with less. The reasons for this are many, but I think are a lot to do with the century-long journey we’ve been on as a society towards wringing every last drop of efficiency out of every last thing. It’s a journey that’s well worth digging into.

This week’s article

The efficiency movement

When it comes to efficiency, how much is too much?

The period from about 1890 to 1920 was a time of great optimism and change in the US. Huge leaps forward were made in industrialisation and agriculture, raising living standards for most of the population. Social reformers sought to eliminate poverty, to improve living conditions in the cities that a growing share of the population lived in, to promote health and well-being, to empower women into the workplace and the electorate, and generally to take the world by the scruff of the neck and drag it kicking and screaming into the modern era. It’s for all these reasons that this period is known as the “Progressive Era”.

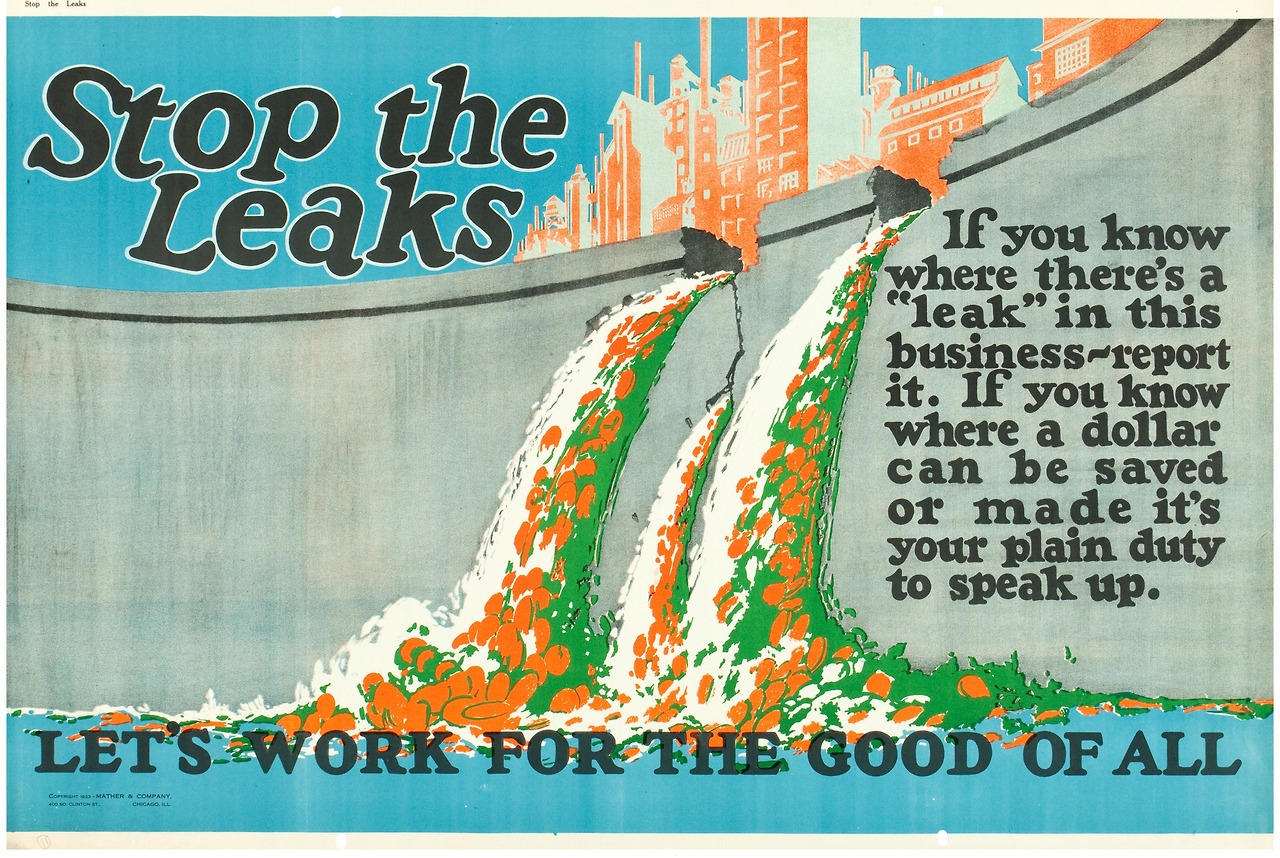

Businesses, and the belief that they could be made significantly more efficient, were a key focus of this optimistic, reforming mindset. The idea emerged that manufacturing activity and trades were capable of being analysed scientifically – measured, studied and improved continuously towards the goal of greater efficiency. “Efficiency” came to be seen as a universally good thing, an end in itself, and the basis of a whole societal campaign. The Efficiency Movement was born.

The reforming zeal of the Efficiency Movement swept America. Its leading lights included Frederick Winslow Taylor, because of whom the principles of scientific management are often called “Taylorism”; Henry Gantt, of “chart” fame; and the inventors of the time-and-motion study, Frank Bunker Gilbreth and Lillian Moller Gilbreth. (The Gilbreths are the subject, with their twelve children, of the book Cheaper By The Dozen; I imagine efficiency becomes fairly critical in a household with twelve kids.)

Efficiency bureaus were set up in cities around the country. Public efficiency officers were appointed to drive efficiency in government, and businesses like Eastman Kodak, Fiat and DuPont restructured themselves entirely to run on the efficiency-obsessed and worker-hostile Bedaux system, created by the eccentric French management consultant and Nazi collaborator Charles Bedaux. The success of the Efficiency Movement is almost impossible to overstate: it’s not unreasonable to call scientific management the defining ideology of the twentieth century, from Teddy Roosevelet to Franklin Roosevelt, from Margaret Thatcher to Tony Blair.

In few places was its influence felt more strongly, though, than in Japan. The efficiency movement was adopted first in the 1920s, where it was promoted by Japanese thinkers including the writer Ikeda Toshiro, who saw inefficiency as a moral failing:

“For certain workers, being late is fundamentally a kind of sickness. This disease can only be cured by intense treatment. If they are not cured by adequate treatment, they will develop a true habitual disease.”

Then, as Japan sought to rebuild its economy from its ruined, post-World War II state, it found it had more than just a moral desire for efficiency. Japan saw increased economic efficiency as the only way to rebuild its economy and its prestige on the world stage; it adopted the principles of the efficiency movement wholesale from the US, and made scientific management the bedrock of its entire postwar economy under the guidance of the occupying American forces and in particular W. Edwards Deming. Deming went to Japan to assist with the 1951 census, but ended up becoming an instrumental figure in Japan’s industrial rebirth and the booming economy that followed.

The ideas cooked up in post-war Japan formed the basis of the lean manufacturing movement, which Japan then re-exported to the world in the late twentieth century, most famously as part of the Toyota Production System. The success of Japanese manufacturing, and the Lean principles on which it was apparently based, ignited a second – and even more intense – efficiency movement that spread rapidly across a business world that was now even more interconnected and interdependent.

What has always underpinned this line of thinking is the belief that businesses are, as a rule, absolutely riddled with waste and inefficiencies. They’re all pathological, and if you were just to take the time to analyse them, you’d discover countless ways to make them more efficient.

There is an existential and irreconcilable disagreement between the scientific manager on the one hand and the craftsperson on the other. The scientific manager thinks everything can always be made more efficient, that there’s always a gain to be made, that progress will never cease. The craftsperson thinks it has to stop somewhere, that you can’t keep insisting that things be made faster and keep paying people less per unit. At some point, something – quality, robustness, or the well-being of the employee – has to give. As Taylor himself wrote:

“After a workman has had the price per piece of the work he is doing lowered two or three times as a result of his having worked harder and increased his output, he is likely entirely to lose sight of his employer’s side of the case and become imbued with a grim determination to have no more cuts if soldiering [marking time, just doing what he is told] can prevent it.”

Only a handful of years ago, the scientific managers seemed to have won the day, banishing the craftspeople to the dustbin of history. The modern workplace was one of measurement, targets, zero inventory, rapid turnarounds, short supply chains, just-in-time production, time-and-motion studies, continuous improvement.

But then the unpredictable happens – an exogenous shock, something that makes things suddenly a little more complicated. Something like Covid, or Brexit. Suddenly, we see the downsides of the drive for efficiency: a lack of robustness, supply chains too finely tuned, a lack of forgiving slack in the system, destructive feedback loops. As Rich Weissman wrote presciently back in March 2020:

“We have become too lean. We are out of inventory on emergency supplies, drugs, medical equipment, cleaning supplies and yes, the ubiquitous toilet paper. Our supply chains are failing, and production is slow to respond.

“Everyone is learning what we in procurement knew all along: We are clueless to the extent, opaqueness and responsiveness of the extended supply chain. Even those manufacturing companies ramping up to meet the demand of masks, gowns, ventilators and hand sanitizer are finding shortages of raw materials.”

It isn’t just complex international supply chains and manufacturing businesses that experienced this; it’s true of all organisations. There’s a fundamental tension between resilience and efficiency, between the scientific manager and the craftsperson.

This tension is, I think, intuitive. The problem is, how do you know where the sweet spot lies? A pendulum always seems to be swinging, it seems. In the good times, when everything’s simple and straightforward and predictable, we push for efficiency and we trim what we see as fat. But we have no idea if we’ve taken it too far, because the good times don’t punish us. The rising tide of efficiency lifts all boats, but it’s only when the tide goes out – as Warren Buffett says – that we see who’s been swimming naked (perhaps because it was more efficient for them not to pack a swimming costume).

What’s clear is that an ideological commitment to efficiency is harmful. It isn’t necessarily true that efficiency gains can always be wrung out of any organisation, certainly not without lowering resilience and increasing risks. We see it in our politics at the moment, as ambulances pile up outside A&E departments while Tory leadership candidates still insist that they’ll obtain magical efficiency gains from the NHS; we see it in our creaking supply chains; we see it in businesses that, faced with a looming recession, make cuts and expect fewer people to do more with less. At some point, something has to give: the only question is what.

Click here to read the article »

This week’s nine interesting links

Generative and AI authored artworks and copyright law

An interesting paper from law professor Michael D. Murray that investigates the question of who owns artworks that are generated by computers and AIs:

“Artists and creatives who mint generative NFTs, collectors and investors who purchase and use them, and art law attorneys all should have a clear understanding of the copyright implications involved with different forms of generative art. This guide seeks to educate each of these audiences and bring clarification to the issues of copyrights in the world of generative art NFTs.”

He concludes that in many cases they are uncopyrightable – including lots that are the basis for lucrative NFT projects. #

How to present to executives

A clear and simple article with some clear and simple advice about how to present to senior executives. It starts, though, with an observation that I think is worth its weight in gold:

“Any given executive is almost always uncannily good at one way of consuming information. They feel most comfortable consuming data in that particular way, and the communication systems surrounding them are optimized to communicate with them in that one way. I think of this as preprocessing reality, and preprocessing information the wrong way for a given executive will frequently create miscommunication that neither participant can quite explain.

“For example, some executives have an extraordinary talent for pattern matching. Their first instinct in any presentation is to ask a series of detailed, seemingly random questions until they can pattern match against their previous experience. If you try to give a structured, academic presentation to that executive, they will be bored, and you will waste most of your time presenting information they won’t consume. Other executives will disregard anything you say that you don’t connect to a specific piece of data or dataset. You’ll be presenting with confidence, knowing that your data is in the appendix, and they’ll be increasingly discrediting your proposal as unsupported.”

There are some general guidelines for how to communicate clearly, but nothing will ever beat figuring out who you’re talking to, understanding how they like to consume information, and tailoring what you present as a result. #

Blind Ambition

I saw this brilliant and inspiring documentary this week: Blind Ambition. It’s directed by Australians Rob Coe and Warwick Ross, who made a 2013 film called Red Obsession about the booming demand for fine wines in China.

This time, they’ve turned their attention to the story of Tongai Joseph Dhafana, Tinashe Nyamudoka, Marlvin Gwese, and Pardon Tagazu. They’re four Zimbabweans who fled the economic meltdown in their home country in the mid-2000s, seeking refuge in neighbouring South Africa. Taking on any kind of work they could, they all ended up in the hospitality industry, where they discovered – completely by chance – an interest in and a talent for wine. They eventually all became sommeliers, getting jobs in top Cape Town restaurants.

By 2017, they’re at the top of their game, and want to enter the wine-tasting olympics: the World Blind Tasting Championships, held each year in Burgundy. And so they start the first-ever Zimbabwean team, a team for a country with no wine-tasting traditions of its own, made up of people who didn’t even encounter wine until well into adulthood. The documentary follows them on their mission to raise enough money to travel to the competition and throughout the competition itself, and it stirring stuff. #

365 Days of Double Exposure – Christoffer Relander

Surreally beautiful double-exposure photographs from the Finnish photographer Christoffer Relander. #

Predicting consumer choices

An interesting paper from David Gal and Itamar Simonson that investigates our ability to predict consumer choices in an age of “big data”.

First, preferences are far from static:

“To be sure, in some cases consumers do have strong, precise, stable preferences for particular products or attributes, and they may habitually buy the same options. For instance, some people prefer to buy a 2% organic milk. Likewise, a few consumers may have self-imposed rule as to the highest price they are willing to pay for a water bottle, which prevents them from buying water at airports. When preferences for products or attributes are strong, stable, and precise, consumer choices are relatively easy to predict, such as by simply asking consumers about their preferences.

“However, most of the choices made by consumers that are not habitual or routine are not the result of precise, stable preferences for those products, but are constructed (or discovered) at the time a decision is being made on the basis of interactions among many individual and situational factors.”

After digging into conjoint analysis, recommendation engines, and other predictive tools, Gal and Simonson conclude:

“In contrast, the conclusions from our review reinforce the view that marketing remains as much an art as science, whether or not the analyses produce seemingly precise numbers. Marketers, as much as ever, must rely on their creativity, insight and judgment, as well as trial and error, and often some serendipity, to identify and develop truly new products (and messages) that match dormant (or “inherent”) consumer preferences.”

Segmentation and strategy: three important truths

A thoughtful post about segmentation from Roger Martin. It’s a controversial subject in the marketing world, having been dissed by Byron Sharp and then written off by his adherents.

Martin reminds us that segmentation is something that’s driven by actual consumers’ actual behaviour, not your own analyses:

“That notwithstanding, customers decide what segment they are in, not you. Big box mass merchandisers (other than Costco, actually) took a while to figure that out. They thought their segment was low-to-middle income families willing to drive to a more distant retailer than their local supermarket to buy goods at a lower price. But Mercedes and BMWs kept showing up in their parking lots. They shouldn’t have been there! They weren’t in the segment. That is half right. They are not in yours, but they are in theirs. And you don’t generate revenues: they do!

“Customers decide whether your offering is a sports car, or not; a cool thing to order at a bar, or not; environmentally friendly, or not. While you are segmenting customers, customers are segmenting you. They create categories, put you in one, and consider you accordingly. You may think their segmentation is nuts, but it just doesn’t matter. Again, you don’t generate revenues: they do.”

He also warns against focusing too hard on the bullseye consumer:

“Many unsuccessful entrepreneurs design an offering that is extremely valuable to the perfect customer – typically themselves – but the drop-off is so steep that their idea collapses, not because it didn’t create value, but because the steepness of the drop-off makes it impossible to make the economics work. Successful entrepreneurs design their offering in a way that appeals to a much broader audience.”

The DALL·E 2 prompt book

Part of the skill of augmented creativity will be writing good prompts for the AI to follow. With that in mind, Guy Parsons of DALL•Ery GALL•Ery showcases some interesting examples, and offers advice about what seems to work and how.

One of the most interesting sections is on the ethical quandaries thrown up by DALL•E’s ability to replicate the styles of individual artists:

“Artists need to make a living. After all, it’s only through the creation of human art to date DALL•E has anything to be trained on! So what becomes of an artist, once civilians like you and I can just conjure up art ‘in the style of [artist]’?

Van Gogh’s ghost can surely cope with such indignities – but living artists might feel differently about having their unique style automagically cloned.”

There are no easy answers, morally or legally. #

Attrition – Joanna Hardy-Susskind

A difficult read from criminal barrister Joanna Hardy-Susskind, explaining just how nightmarish conditions at the criminal bar have become (hence the recent strikes):

“The finances have never kept pace with the fight. With what is required of me. With what is required of the mass of legally-aided barristers who ultimately have to rely on successful partners, generous families or sheer luck to get by. But, money aside, it is the conditions that deliver the sucker punch. Without a HR department the job takes and takes. There is no yearly appraisal. No occupational health appointment. No intervention. No one to assess the toll. There is a high price to be paid for seeing photos of corpses, for hearing the stories of abused children and for sitting in a windowless cell looking evil in the eye. There are no limits as to how much or how often you can wreck your well-being, your family life, your boundaries. No limit to how many blows the system will strike to your softness. The holidays you will miss, the occasions you will skip, the people you will let down. The thing about words is that they sometimes fail you. When you emerge from a 70-hour week and notice the look in the eyes of the proud parents who propelled you here – but miss you now.”

Inside the far right’s growing obsession with art

Twitter is awash with “traditionalist” art accounts that profess a yearning for simpler times. They mostly feature figurative paintings, architecture from the gothic to the baroque, lots of Greco-Roman sculpture and, of course, lots of white people.

James Greig argues that this isn’t just philistinism; it’s part of a broader sweep of far-right propaganda, rooted in our current politics:

“By comparing modern art with conventional depictions of rural scenes and able-bodied white people, this digital subculture is expressing a specific hierarchy of values. It’s about returning to a lost halcyon age of (implicitly white) western civilisation, which is sometimes Ancient Greece, sometimes the Renaissance, and sometimes Mad Men. It expresses a desire to return to ‘the natural order of things’, which has been degraded by modernity and multiculturalism, and conceptualises beauty as something which is eternal and objective.”